🔗 There are two very different things called “package managers”

Earlier today, Ludovic Courtès asked these questions on Mastodon:

Are npm/crates.io just a different approach to distributing software, compared to Linux distros?

Or is there something more fundamental about their approach, how it affects user/developer relations, and how if affects user autonomy?

My take on these questions is that to me there are two fundamental differences:

1) npm/crates.io/LuaRocks (language package managers) are package managers for programmers. They ship primarily modules/libraries; apt/rpm/etc (system package managers) are package managers for end-users. I don’t expect a non-programmer to ever use cargo but I expect a Ubuntu user to use apt (even if via a GUI).

2) language package managers cut the “middleman” and allow module/library devs to make them available to other devs right away, without someone like a Debian developer having to deem them relevant/ready enough for packaging.

The fact that there is no curation is a feature for language package managers, just like the fact that there is curation is a feature for system package managers.

The reason why system package managers are curated is for end-user protection. The reason why language package managers are not curated is to provide developer autonomy. There is a wide gradient between these two things.

If as a developer you put too many hurdles between me and the library I want to use in the name of “protecting” me, I’m gonna skip your package manager and just fetch my dependencies from the upstream source.

For end-users just trying to keep their browser up-to-date, I understand the story is completely different.

There are other practical reasons why developers use language-specific package managers, of course. One of them is dealing with dependency versioning. By having per-project trees (think of node_modules in npm), each project can define their own dependency versions, regardless of what is available system-wide (if it is available at all). This is something that happens in practice, but that is not necessarily a fundamental design difference between language and system manager. In our 2019 paper we discussed alternatives, but the approaches we suggested there are not the general state of the world today.

An aside: when talking about projects adopting or not certain package managers, one needs to keep an eye for the motivations. I’ve seen questionable arguments from companies keeping packages away from community repos (for example, to retain control over download metrics). But in my experience, I’ve only ever seen this happening to system package managers, but never to language package managers, which just seem to reiterate how different these two universes are.

In an ideal world, system package managers and language package managers would be able to cross-reference each other to avoid the duplication of packaging work we see everywhere. This is something we talked about in the paper linked above. In fact, I’ve been trying to preach the gospel of cross-language links across ecosystems since at least… *checks git, or rather, cvs history*… 2003.

I’m as sympathetic to the ideal as they come, but the reality is that we need to deal with these two universes for now (…for a significant definition of “now”).

Amidst the lively debate in Mastodon, my friend Julio brought up the elephant in the room:

(puts Diogenes beard):

“Docker.”

…to which I can only nod my head in agreement and say: the success of Docker is the developer world’s tacit acknowledgement that package management has failed.

(For anyone else reading this tongue-in-cheek comment without further context: I have authored two package managers, both in the language side and distro side of the game. If that remark feels excessive, just s/has failed/is hard/, but my point still stands.)

Don’t get me wrong, package management has evolved greatly over the years, but as a community we’re still understanding it. There are two very different things that are both called package managers, and they serve different purposes. Another world is possible, but it will take a lot of gradual change, and “if only everyone would adopt my package manager where everything works” is not a solution (that applies to people living inside the bubble of their own language ecosystem as well!). Age has turned me from a revolutionary into a reformist.

🔗 Last day at Kong

Today is my last day at Kong!

Posts like this tend to be cliché, with the usual adjectives and thank-yous. I’ve already thanked many people in person (err, Zoom!) already, so I thought I’d take this opportunity instead to celebrate all we’ve achieved together.

I feel very proud to have had the chance to work on an open-source project of this scale. The stories we’ve heard through the years really bring home the positive impact these lines of code we wrote together have had on literally billions of people.

So I look back at those commit graphs, and they tell the story not only of lines of code, but of all of the teamwork that went into getting them out there.

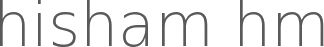

I look at these graphs and I see the earliest days in 2017 joining our newly-formed Core Team fronted by Thibault Charbonnier, taking over from the two-man-show that was him and Marco Palladino (who’s still ahead of me in the contributions ranking! — though I’m happy we’re both now overtaken by Aapo Talvensaari!). I see Kong going 1.0, then me taking the mantle as the team’s tech lead driving Kong to 2.0 and beyond, doing whatever was needed to try and help the project forward (even PM at times!). I see my 2021 sabbatical and I see Guanlan Dai bringing me back to take on a new project.

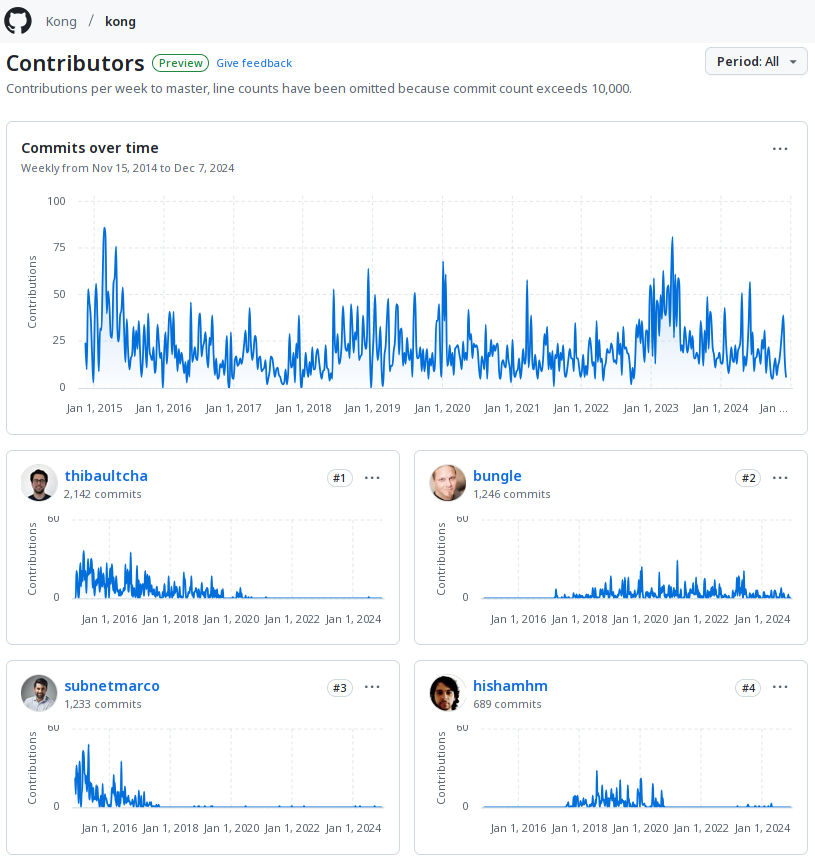

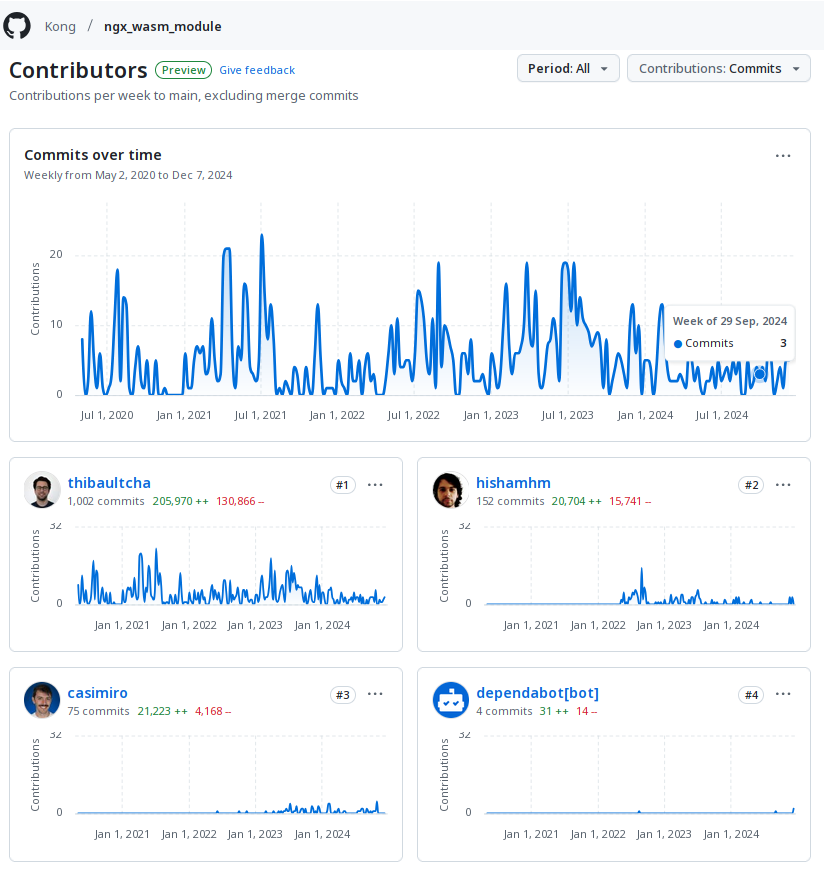

I look at these graphs and I see myself once again working alongside Thibault, this time in the WasmX team, helping him and Caio Casimiro make WebAssembly support in Kong a reality. Finally, I see the time I’ve put in design (which does not show in the commit graphs!) and implementation (which does!) for my final project at the company, DataKit, which is just coming out now. In short, I look at these graphs and I see Kong’s past, present and future!

Commits and lines of code barely begin to tell the story, though. In one of my very earliest days, my first manager at the company, Geoff Townsend, asked me what was my main motivation driver: the “what”, the “why”, the “how” or the “who”. I’m always amused when I remember his surprised reaction when I immediately said: the “who”. I’m a team player first and foremost, and there’s no way I could properly give shout-outs to everyone, but there’s been great people around me every step of the way, from the very first incarnation of the Core Team led by Geoff (Thibault, Aapo, Enrique García Cota, Thijs Schreijer) to the most recent incarnation of the WasmX team led by Robert Serafini (Thibault, Caio + Michael Martin, Vinicius Mignot, Brent Yarger). By shouting out my first and last engineering teams, I hope they represent all Kongers past and present who I’ve ever crossed paths with, and through them I thank you all!

Since I ended up doing thank-yous, I guess I’ll have to do the adjectives too! Kong was a fun, challenging and fulfilling adventure, and I leave feeling accomplished. A new challenge awaits me, so in the wise words of Dave Grohl, “done! and on to the next one!” 🤘

Follow

🐘 Mastodon ▪ RSS (English), RSS (português), RSS (todos / all)

Last 10 entries

- Aniversário do Hisham 2025

- The aesthetics of color palettes

- Western civilization

- Why I no longer say "conservative" when I mean "cautious"

- Sorting "git branch" with most recent branches last

- Frustrating Software

- What every programmer should know about what every programmer should know

- A degradação da web em tempos de IA não é acidental

- There are two very different things called "package managers"

- Last day at Kong