🔗 Again on 0-based vs. 1-based indexing

André Garzia made a nice blog post called “Lua, a misunderstood language” recently, and unfortunately (but perhaps unsurprisingly) a bulk of HN comments on it was about the age-old 0-based vs. 1-based indexing debate. You see, Lua uses 1-based indexing, and lots of programmers claimed this is unnatural because “every other language out there” uses 0-based indexing.

I’ll brush aside quickly the fact that this is not true — 1-based indexing has a long history, all the way from Fortran, COBOL, Pascal, Ada, Smalltalk, etc. — and I’ll grant that the vast majority of popular languages in the industry nowadays are 0-based. So, let’s avoid the popularity contest and address the claim that 0-based indexing is “inherently better”, or worse, “more natural”.

It really shows how conditioned an entire community can be when they find the statement “given a list x, the first item in x is x[1], the second item in x is x[2]” to be unnatural. :) And in fact this is a somewhat scary thought about groupthink outside of programming even!

I guess I shouldn’t be surprised by groupthink coming from HN, but it was also alarming how a bunch of the HN comments gave nearly identical responses, all linking to the same writing by Dijkstra defending 0-based indexing as inherently better, as an implicit Appeal to Authority. (Well, I did read Dijkstra’s note years ago and wasn’t particularly convinced by it — not the first time I disagree with Dijkstra, by the way — but if we’re giving it extra weight for coming from one of our field’s legends, then the list of 1-based languages above gives me a much longer list of legends who disagree — not to mention standard mathematical notation which is rooted on a much greater history.)

I think that a better thought, instead of trying to defend 1-based indexing, is to try to answer the question “why is 0-based indexing even a thing in programming languages?” — of course, nowadays the number one reason is tradition and familiarity given other popular languages, and I think even proponents of 0-based indexing would agree, in spite of the fact that most of them wouldn’t even notice that they don’t call it a number zero reason. But if the main reason for something is tradition, then it’s important to know how did the tradition start. It wasn’t with Dijkstra.

C is pointed as the popularizer of this style. C’s well-known history points to BCPL by Martin Richards as its predecessor, a language designed to be simple to write a compiler for. One of the simplifications carried over to C: array indexing and pointer offsets were mashed together.

It’s telling how, whenever people go into non-Appeal-to-Authority arguments to defend 0-based indexes (including Dijkstra himself), people start talking about offsets. That’s because offsets are naturally 0-based, being a relative measurement: here + 0 = here; here + 1 meter = 1 meter away from here, and so on. Just like numeric indexes are identifiers for elements of an ordered object, and thus use the 1-based ordinal numbers: the first card in the deck, the second in the deck, etc.

BCPL, back in 1967, made a shortcut and made it so that p[i] (an index) was equal to p + i an offset. C inherited that. And nowadays, all arguments that say that indexes should be 0-based are actually arguments that offsets are 0-based, indexes are offsets, therefore indexes should be 0-based. That’s a circular argument. Even Dijkstra’s argument also starts with the calculation of differences, i.e., doing “pointer arithmetic” (offsets), not indexing.

Nowadays, people just repeat these arguments over and over, because “C won”, and now that tiny compiler-writing shortcut from the 1960s appears in Java, C#, Python, Perl, PHP, JavaScript and so on, even though none of these languages even have pointer arithmetic.

What’s funny to think about is that if instead C had not done that and used 1-based indexing, people today would certainly be claiming how C is superior for providing both 1-based indexing with p[i] and 0-based pointer offsets with p + i. I can easily visualize how people would argue that was the best design because there are always scenarios where one leads to more natural expressions than the other (similar to having both x++ and ++x), and how newcomers getting them mixed up were clearly not suited for the subtleties of low-level programming in C, and should be instead using simpler languages with garbage collection and without 0-based pointer arithmetic.

🔗 User power, not power users: htop and its design philosophy

What the principles that underlie the software you make?

This short story is not really about htop, or about the feature request that I’ll use as an illustration, but about what are the core principles that drive the development of a bit of software, down to every last detail. And by “core principles” I really mean it.

When we develop software, we have to make a million decisions. We’re often driven by some unspoken general principles, ranging from our personal aesthetics on the external visuals, to our sense of what makes a good UX in the product behavior, to things such as “where does bloat cross the line” in the engineering internals. In FOSS, we’re often wearing all these hats at the same time.

We don’t always have it clear in our mind what drives those principles, we often “just know”. There’s no better opportunity to assess those principles than when user feedback asks for a change in the behavior. And there’s no better way to explain to yourself why the change “feels wrong” than to put those principles in writing.

Today was one such opportunity.

I was peeking at the htop issue tracker as an end-user, which is a refreshing experience, having recently retired from this FOSS project I started. I spotted a feature request, asking for a change to make it hide threads by default.

The rationale was sensible:

People casually using htop usually have no idea what userland threads are for.

People who actually need to see them can easily enable them via SHIFT+H.With them currently enabled by default, it is very inconvenient to go through the list and see what is running, taking up RAM, CPU usage and whatnot, therefore I think it’d be more user-friendly to not show them by default.

He proceeded to show two screenshots: one with the default behavior, full of threads (in green) mixed with the processes, and another with threads disabled.

When one of the current developers said that it’s easier for the user to figure out how to hide things than for them to discover that something hidden can be shown, the counter-argument was also sensible:

Htop can also show Disk IO, which can be arguably very useful, but is hidden by default.

At that point, I decided to put my “original author” hat on to explain what was the intent behind the existing behavior. Here’s what I wrote:

Hi @C0rn3j, I thought I’d drop by and give a bit of historical background as to what was my motivation for showing threads by default.

People casually using htop usually have no idea what userland threads are for.

Yes! I fully sympathize with this sentiment. And the choice for enabling threads and painting them green was deliberate.

You have no idea how many times I was asked “hey, why are some processes green?” over these 15+ years — and no, it wasn’t annoying: each of these times it was an opportunity to teach someone about threads!

htop was designed to provide a view to what’s going on in the system. If a process is spawning threads like crazy, or if all your cores are overwhelmed because multiple threads of a process are doing work, I think it’s fair to show it to the user, even if they don’t know a thing about threads — or I would say, especially if they don’t know a thing about threads, otherwise these things would be happening and they wouldn’t even know where to look.

Htop can also show Disk IO, which can be arguably very useful, but is hidden by default.

One of my last projects when I was still active in htop development was to add tabs to the interface, so that the user would have a more discoverable path for navigating through these additional columns:

This code is in the next branch of the old repo https://github.com/hishamhm/htop/ — I think the code for tabs is actually finished (though not super tested); it’s pretty nice, you can click on them or cycle with the Tab key, but the Perf Counters support which I was working on, never really got stable to a point of my liking, and that’s when I got busy with other things and drifted away from development — turns out I enjoy writing interface code a lot more than the systems monitoring part!

Anyway, I think that also illustrates the pattern that went into the design: I implemented the entire tabs feature because I wanted to make IO and Perf Counters more discoverable. I wanted to put that information in front of users faces, especially for users who don’t know about these things! I considered the fact that I had implemented the entire functionality of iotop inside htop but people didn’t know about it to be a personal failure, and a practical learning experience: adding systems functionality is useless if the UI design doesn’t get it to users’ hands. (And even I didn’t use the IO features because there was no convenient way of using them.)

I never wanted to implement a tool for “super advanced Linux power users who know what they doing”, otherwise I would have never spent a full line at the bottom showing F-keys, and I would have spent my time implementing Vim bindings (ugh ;) ) instead of mouse support. I’ve always made a point that every setting can be settable via the Setup screen, which you can access via F2-Setup (shown at the bottom line!) and which you can control with the keyboard or mouse, no “edit this config file to use this advanced feature for the initiated only” or even “read the man page” (in fact it only has a man page because Debian developers contributed it!).

I wanted to make a tool that has the power but doesn’t hide it from users, and instead invites users into becoming more powerful. A tool that reaches out its hand and guides them along the way, helping users to educate themselves about what’s happening on the internals of their system, and in this way have more control of it. This is how you hand power to users, not by erecting barriers of initiation or by giving them the bare minimum they need. I reject this dicothomy between “complicated tools for power users” and “stripped-down tools for mere mortals”, the latter being a design paradigm made popular by certain companies and unfortunately copied by so many OSS GUI projects, without realizing what the goals of that paradigm really were, but that’s another rant.

And that’s why threads are enabled by default, and colored in green!

(PS: and to put the point to the proof, I must say that the tabs feature was a much bigger code change than Perf Counters themselves; it included some quite big internal refactors (there’s no “toolkit”, everything is drawn “by hand” by htop) with unfortunately might make it difficult to ressurect that code (or not! who knows?), and of course tabs are user-definable and user-editable!)

The user who proposed the change in the defaults thanked me for the history tidbits and closed the feature request. But in some sense writing this down was probably more enlightening to me than it was for them.

When I started writing htop, I did not set out to create “an instrument for user empowerment” or any such lofty goal. (All I wanted was to have a top that scrolled and was more forgiving with mistypes than circa-2005 top!) But as I proceeded to write the software, every small decision had to come from somewhere, even if done without much deliberate thought, even if at the time it was just “it felt right”. That’s how your principles start to percolate into the project.

Over time, the picture I described in that reply above became clear to me. It helped me build practical guidelines, such as “every setting must be UI-accessible”, it helped me prioritize or even reject feature requests based on how much they aligned to those principles, and it helped me build a sense of purpose for the software I was working on.

If you don’t have it clear to yourself what are the principles that are foundational to the software you’re building, I recommend you to give this exercise a try — try to explain why the things in the software are the way they are. There are always principles, even if they are not conscious to you at the moment.

(PS: It would be awesome if some enterprising soul would dig down the tab support code and ressurrect it for htop 3! I don’t plan to do so myself any time soon, but all the necessary bits and pieces are there!)

🔗 Talking htop at the Changelog podcast

I was interviewed at the Changelog podcast about the surprising story of the maintainership transition in htop:

The Changelog 413: How open source saved htop – Listen on Changelog.com

🔗 Protests and the space launch

I am not going to talk directly about the US protests. Instead, I will briefly note the role of the State in them, both as cause—promoting institutional racism—and as a continuing instigator. But aren’t the protests for justice, which supposedly needs to come from the State? But the government is clearly not interested in justice. So we have on one side the people, on the other side the State. But it didn’t have to be this way by definition: it’s _this_ particular state that’s the problem. And this makes me think of Peter Thiel.

Peter Thiel has said, in no uncertain terms, that he does not believe in democracy and ultimately wants the destruction of any form of State. That’s what he went up on stage in the elections for. That’s what the alt-right stands for. This is not a crisis, this is an ongoing plan. Historians will look at this as a multi-decade process, with the early 1980s under Reagan and Thatcher as the first inflection point, and the last few years with the alt-right, Trump and Brexit as the second one.

The first stage, neoliberalism, was about crippling the state in order to declare it inefficient and privatize it. In the 90s in particular this was sped up in practice and played down in discourse, but early on this was the stated goal.

Now at the second stage, it is no longer about crippling government institutions. It is about crippling the concept of government itself: get the incompetent to power, so that the supposed flaws of the democratic model become evident. Then offer something else.

Of course, the trickery there is that invariably the incompetent were led to power in various places by apparently legal but effectively criminal means: mass propaganda done in breach of campaign funding laws, voter supression, buying congress.

So now we’re at the stage where there’s a useful minority of radicalized fascists ensuring we get the worst possible government, and a mass of average people whose heroes are billionaires, ranging from your monopolist-turned-philantropist to your tweeting-techbro bigot. It may seem contradictory that the forces that are ultimately destroying the notion of nation-state ostensibly employ the discourse of nationalism. But if you pay attention, they are priming their base on adapting to the upcoming state of things.

This pandemic is the first time in history when we see a national crisis being addressed by the government by giving a press release and giving names of _companies_ who are going to be doing this and that to deal with the issue. This was very, very startling to see.

The notion that is up for companies and not the state to organize society is being normalized. America is at the forefront of this process, and has been for a long time. Other places still have things like functioning health and educational systems, but the pressure exists. In that sense, the landmark space launch — once a matter of national pride, now privatized into another triumph of business over country — led by Thiel’s associate Musk, is not at all disconnected from the ongoing events. They are deeply, closely connected.

Thiel’s company Palantir — named after the all-seeing eye in LOTR, another techbro favorite — provides machinery for mass surveillance in the the US. The surveillance people worldwide are under is already managed by a private company.

When you think of Russia and its oligarchs, or the growing number of billionaires in China’s parliament — why lobby the middleman, just buy a Congress seat for yourself — we see that the increasingly direct control of superpowers by businessmen is not an American-only phenomenon. It might be that the façade of a state will stick around for long, as a useful device as people cling to their flags and anthems, but I feel the foundations of the modern nation-state slowly crumble into dust under my feet, and I do not like what’s taking its place.

Zygmunt Bauman saw it back in the 1990s: in a world of companies, we’re no longer citizens, only consumers. And the rippling effects of this are much worse than they initially sound, but this is a conversation for another time.

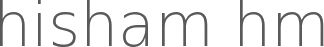

🔗 Remembering Windows 3.1 themes and user empowerment

This reminiscence started reading a tweet that said:

Unpopular opinion: dark modes are overhyped

Windows 3.1 allowed you to change all system colors to your liking. Linux been fully themeable since the 90s. OSX came along with a draconian “all blue aqua, and maybe a hint of gray”.

People accepted it because frankly it looked better than anything else at the time (a ton of Linux themes were bad OSX replicas). But it was a very “Ford Model T is available in any color as long as it’s black” thing.

The rise of OSX (remember, when it came along Apple had a single-digit slice of the computer market) meant that people eventually got used to the idea of a life with no desktop personalization. Nowadays most people don’t even change their wallpapers anymore.

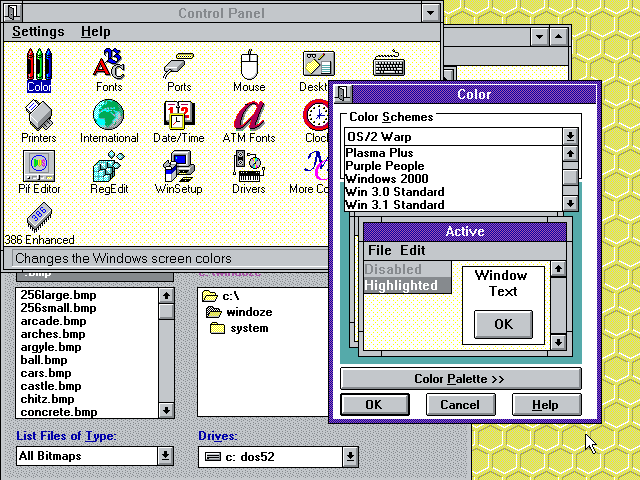

In the old days of Windows 3.1, it was common to walk into an office and see each person’s desktop colors, fonts and wallpapers tuned to their personalities, just like their physical desk, with one’s family portrait or plants.

|

|

|

I just showed the above screenshots to my sister, and she sighed with a happy nostalgia:

— Remember changing colors on the computer?

— Oh yes! we would spend hours having fun on that!

— Everyone’s was different, right?

— Yes! I’d even change it according to my mood.

Looking back, I feel like this trend of less aesthetic configurability has diminished the sense of user ownership from the computer experience, part of the general trend of the death of “personal computing”.

I almost wrote that a phone UI allows for more self-expression today than a Win/Mac computer. But then I realized how much I struggled to get my Android UI the way I wanted, until I installed Nova Launcher that gave me Linux-levels of tweaking. The average user does not do this.

But at least they are more likely to change wallpaper in their phones than their computers. Nowadays you walk into an office and all computers look the same.

The same thing happened to the web, as we compare the diminishing tweakability of a MySpace page to the blue conformity a Facebook page, for example.

Conformity and death of self-expression are the norm, all under the guise of “consistency”.

User avatars forced into circles.

App icons in phones forced into the same shape.

Years ago, a friend joked that the inconsistency of the various Linux UI toolkits was how he felt the system’s “freedom”. We all laughed and wished for a more consistent UI, of course. But that discourse on consistency was quickly coopted to remove users’ agency.

What begins with aesthetics and the sense of self-expression, continues to a lack of ownership of the computing experience and ends in the passive acceptance of systems we don’t control.

Changes happen, but those are independent from the users’ wishes, and it’s a lottery whether the changes are for better or for worse.

Ever notice how version changes are called “updates” and not “upgrades” anymore?

In that regard, I think Dark Mode is a welcome addition as it allows a tiny bit of control and self-expression to the user, but it’s still kinda sad to see how far we regressed overall.

The hype around it, and how excited users get when they get such crumbles of configurability handed to them, just comes to show how users are unused to getting any degree of control back in their hands.

Follow

🐘 Mastodon ▪ RSS (English), RSS (português), RSS (todos / all)

Last 10 entries

- Aniversário do Hisham 2025

- The aesthetics of color palettes

- Western civilization

- Why I no longer say "conservative" when I mean "cautious"

- Sorting "git branch" with most recent branches last

- Frustrating Software

- What every programmer should know about what every programmer should know

- A degradação da web em tempos de IA não é acidental

- There are two very different things called "package managers"

- Last day at Kong