🔗 Remembering Windows 3.1 themes and user empowerment

This reminiscence started reading a tweet that said:

Unpopular opinion: dark modes are overhyped

Windows 3.1 allowed you to change all system colors to your liking. Linux been fully themeable since the 90s. OSX came along with a draconian “all blue aqua, and maybe a hint of gray”.

People accepted it because frankly it looked better than anything else at the time (a ton of Linux themes were bad OSX replicas). But it was a very “Ford Model T is available in any color as long as it’s black” thing.

The rise of OSX (remember, when it came along Apple had a single-digit slice of the computer market) meant that people eventually got used to the idea of a life with no desktop personalization. Nowadays most people don’t even change their wallpapers anymore.

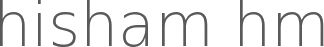

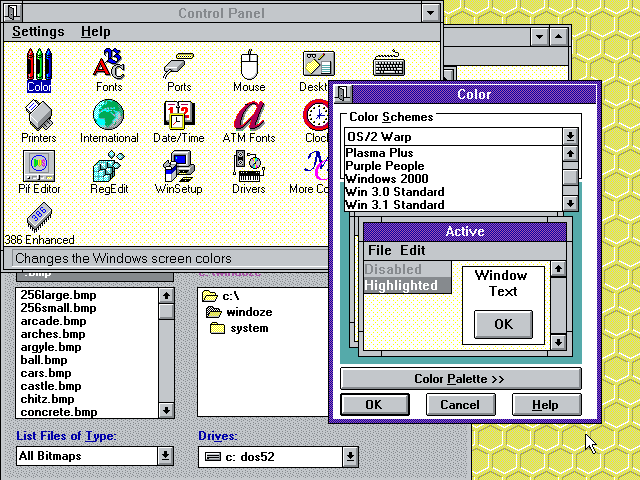

In the old days of Windows 3.1, it was common to walk into an office and see each person’s desktop colors, fonts and wallpapers tuned to their personalities, just like their physical desk, with one’s family portrait or plants.

|

|

|

I just showed the above screenshots to my sister, and she sighed with a happy nostalgia:

— Remember changing colors on the computer?

— Oh yes! we would spend hours having fun on that!

— Everyone’s was different, right?

— Yes! I’d even change it according to my mood.

Looking back, I feel like this trend of less aesthetic configurability has diminished the sense of user ownership from the computer experience, part of the general trend of the death of “personal computing”.

I almost wrote that a phone UI allows for more self-expression today than a Win/Mac computer. But then I realized how much I struggled to get my Android UI the way I wanted, until I installed Nova Launcher that gave me Linux-levels of tweaking. The average user does not do this.

But at least they are more likely to change wallpaper in their phones than their computers. Nowadays you walk into an office and all computers look the same.

The same thing happened to the web, as we compare the diminishing tweakability of a MySpace page to the blue conformity a Facebook page, for example.

Conformity and death of self-expression are the norm, all under the guise of “consistency”.

User avatars forced into circles.

App icons in phones forced into the same shape.

Years ago, a friend joked that the inconsistency of the various Linux UI toolkits was how he felt the system’s “freedom”. We all laughed and wished for a more consistent UI, of course. But that discourse on consistency was quickly coopted to remove users’ agency.

What begins with aesthetics and the sense of self-expression, continues to a lack of ownership of the computing experience and ends in the passive acceptance of systems we don’t control.

Changes happen, but those are independent from the users’ wishes, and it’s a lottery whether the changes are for better or for worse.

Ever notice how version changes are called “updates” and not “upgrades” anymore?

In that regard, I think Dark Mode is a welcome addition as it allows a tiny bit of control and self-expression to the user, but it’s still kinda sad to see how far we regressed overall.

The hype around it, and how excited users get when they get such crumbles of configurability handed to them, just comes to show how users are unused to getting any degree of control back in their hands.

🔗 An annoying aspect of Lua’s if-based error checking

Lua does not have error checking/propagation primitives (like `?` or `!` operators in newer languages). The usual convention is to use plain old `if` statements:

local ok, err = do_something() if err then return nil, err end

So any call that propagates an error ends up at least 4 lines long. This has an impact on the programmer’s “threshold” for deciding that something is worth refactoring into a function as opposed to programming-by-copy-and-paste.

(An aside: I know that in recent years it has been trendy to defend copy-and-paste programming as a knee-jerk response against Architecture Astronauts who don’t know the difference between abstraction and indirection layers — maybe a topic for another blog post? — but, like the Astronauts who went too far in one direction by following a mantra without understanding the principles, the copy-pasters are now too far in the other direction, leading to lots of boilerplate code that looks like productivity but can pile up into a mess.)

So, today I had a bit of code that looked like this:

local gpg = cfg.variables.GPG local gpg_ok, err = fs.is_tool_available(gpg, "gpg") if not gpg_ok then return nil, err end

When I had to do the same thing in another function, the immediate reaction was to try to turn this into a nice five-line function and just `local gpg = get_gpg()` in both places. However, when we account to error checking, this would end up amounting to:

local function get_gpg()

local gpg = cfg.variables.GPG

local gpg_ok, err = fs.is_tool_available(gpg, "gpg")

if not gpg_ok then

return nil, err

end

return gpg

end

local function foo(...)

local gpg, err = get_gpg()

if not gpg then

return nil, err

end

...

end

local function bar(...)

local gpg, err = get_gpg()

if not gpg then

return nil, err

end

...

end

where as the “copy-paste” version would look like:

local function foo(...)

local gpg = cfg.variables.GPG

local gpg_ok, err = fs.is_tool_available(gpg, "gpg")

if not gpg_ok then

return nil, err

end

...

end

local function bar(...)

local gpg = cfg.variables.GPG

local gpg_ok, err = fs.is_tool_available(gpg, "gpg")

if not gpg_ok then

return nil, err

end

...

end

It is measurably less code. But it spreads the dependency on the external `cfg` and `fs` modules in two places, and adds two bits of code must remain in sync. So the shorter version is less maintainable, or in other words, more bug-prone in the long run.

It is unfortunate that overly verbose error handling drives the programmer towards the worse choice software-engineering-wise.

🔗 Splitting a Git commit into one commit per file

Sometimes when working on a branch, you end up with a “wip” or “fixup” commit that contains changes to several files:

01a25e6 introduce raccoon library bd197ac modify core to use raccoon 02890e3 add --raccoon option to the CLI f938740 fixes fab9379 add documentation on raccoon features

Our f938740 fixes commit has changes that really belong in the three previous commits. Before merging, we want to squash those changes in the original commits where the correct code should have been in the first place.

The typical way to do this is to use interactive rebase, using git rebase -i.

This is not a post explaining interactive rebase, so check out some other sources before proceeding if you are not familiar with it!

Splitting things from a “fixup” commit can get tedious using git rebase -i in conjunction with the edit option and git add -p, especially when you really know that all changes to a file belong to a certain commit.

Here’s a quick script for the rescue: it is designed to be used during an interactive rebase, and splits the current commit into multiple commits, one with the contents of each file:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

message="$(git log --pretty=format:'%s' -n1)"

if [ `git status --porcelain --untracked-files=no | wc -l` = 0 ]

then

git reset --soft HEAD^

fi

git status --porcelain --untracked-files=no | while read status file

do

echo $status $file

if [ "$status" = "M" ]

then

git add $file

git commit -n $file -m "$file: $message"

elif [ "$status" = "A" ]

then

git add $file

git commit -n $file -m "added $file: $message"

elif [ "$status" = "D" ]

then

git rm $file

git commit -n $file -m "removed $file: $message"

else

echo "unknown status $file"

fi

done

Save this as split-files.sh (and make it executable with chmod +x split-files.sh).

Now, we proceed with the interactive rebase. When doing an interactive rebase, Git will open a text editor: in the commit you want to split, replace pick with edit:

pick 01a25e6 introduce raccoon library pick bd197ac modify core to use raccoon pick 02890e3 add --raccoon option to the CLI edit f938740 fixes pick fab9379 add documentation on raccoon features # Rebase 01a25e6..fab9379 onto cb370a2 (5 commands) # # Commands: # p, pick= use commit # r, reword = use commit, but edit the commit message # e, edit = use commit, but stop for amending # ...

When you save and exit the text editor launched by Git, you will return to the prompt with the repo's HEAD pointing at the commit we will split. Then run ./split-files.sh and then git rebase --continue.

Now launch the interactive rebase again. Your commits should look like this:

pick 01a25e6 introduce raccoon library pick bd197ac modify core to use raccoon pick 02890e3 add --raccoon option to the CLI pick 8369783 src/lib/racoon.foo: fixes pick a3c4e42 src/cli/foobar: fixes pick 108a931 src/core/core.foo: fixes pick fab9379 add documentation on raccoon features # Rebase 01a25e6..fab9379 onto cb370a2 (7 commands) # # Commands: # p, pick= use commit # r, reword = use commit, but edit the commit message # e, edit = use commit, but stop for amending # ...

The "fixes" commit in our example was split into three. Now move these new commits around and use the fixup command to merge them to the commit immediately above it:

pick 01a25e6 introduce raccoon library fixup 8369783 src/lib/racoon.foo: fixes pick bd197ac modify core to use raccoon fixup 108a931 src/core/core.foo: fixes pick 02890e3 add --raccoon option to the CLI fixup a3c4e42 src/cli/foobar: fixes pick fab9379 add documentation on raccoon features # Rebase 01a25e6..fab9379 onto cb370a2 (7 commands) # # Commands: # p, pick= use commit # r, reword = use commit, but edit the commit message # e, edit = use commit, but stop for amending # ...

Save, exit, and we're done! But a word of warning: when moving commits around make sure there are no other commits that change the same part of the file in between your "fixes" commit and the one you're squashing it into. When in doubt, Gitk and similar tools make it easier to check this before you jump into squashing commits.

If everything went well, our history now looks like this:

8370e83 introduce raccoon library 038c5a3 modify core to use raccoon bb9783a add --raccoon option to the CLI fab9379 add documentation on raccoon features

The SHA hashes of the commits have changed, because they now contain the fixes merged into them, and the separate catch-all "fixes" commit is now gone for good!

Of course this is a bit of an ideal scenario where each file goes neatly into a separate commit. Sometimes changes made to a single file belong in separate commits. In those cases, the solution is a bit more manual, using edit and then git add -p, which is super useful.

And remember, if any moment you messed up, git reflog is your best friend! But this is a topic for another time. Cheers!

🔗 Lua string concatenation considered not harmful

A user in the Lua mailing list recently asked the following question:

yield( splits[i-1][1]..word[i+1]..word[i]..splits[i+2][2] )

I tried table.concat and string.format, but both perform worst. This was

counter-intuitive to me, because Lua string concat generates copies of

intermediate strings. However, seems that for short strings and small number

of concatenated strings, string __concat performs better than string.format

or table.concat. Does anyone know if my observation is true?

The “folk wisdom” about copies of intermediate strings in Lua is often mis-stated, I think.

("aa"):upper() .. ("bb"):upper() .. ("cc"):upper() .. ("dd"):upper()

It translates to a single concatenation bytecode in both Lua and LuaJIT, so it produces the following strings in memory over the course of its execution:

"aa" "bb" "cc" "dd" "AA" "BB" "CC" "DD" "AABBCCDD"

This, on the other hand, does generate intermediate strings:

local s = ""

for _, w in ipairs({"aa", "bb", "cc", "dd"})

s = s .. w:upper()

end

It produces

"" "aa" "bb" "cc" "dd" "AA" "BB" "CC" "DD" "AABB" "AABBCC" "AABBCCDD"

Notice the little pyramid at the end. This pattern is the one that people tell to avoid when they talk about “intermediate strings”. For a loop like that, one should do instead:

local t = {}

for _, w in ipairs({"aa", "bb", "cc", "dd"})

table.insert(s, w:upper())

end

local s = table.concat(t)

That will produce:

"aa" "bb" "cc" "dd" "AA" "BB" "CC" "DD" "AABBCCDD"

plus an extra table. Of course this is an oversimplified example for illustration purposes, but often the loop is long and the naive approach above can produce a huge pyramid of intermediate strings.

Over the years, the sensible advice was somehow distorted into some “all string concatenation is evil” cargo-cult, but that is not true, especially for short sequences of concatenations in an expression. Using a..b..c will usually be cheaper and produce less garbage than either string.format(”%s%s%s”, a, b, c) or table.concat({a, b, c}).

🔗 LuaRocks 3.0.0beta1

I am extremely happy to announce LuaRocks 3.0.0beta1, the almost-finished package for the new major release of LuaRocks, the Lua package manager.

First of all: “Why beta1?” — the code itself is release-candidate

quality, but I decided to call this one beta1 and not rc1 because the

Windows package is not ready yet, and I wanted to get some early

feedback on the Unix build while I complete the final touches of the

Windows package.This is NOT going to be a long-or-endless beta cycle: if no major

showstoppers are reported, the final 3.0.0 release, including Unix and

Windows packages, is expected to arrive in one week. But please, if

you want to help out with LuaRocks, give this beta1 a try and report

any findings!

Yes, it’s finally here! After a way-too-long gestation period, LuaRocks 3 is about ready to see the light of day. And it includes a lot of new stuff:

- New rockspec format

- New commands, including `luarocks init` for per-project workflows

- New flags, including `–lua-dir` and `–lua-version` for using

- multiple Lua installs with a single LuaRocks

- New build system, gearing towards a new distribution model

- General improvements, including namespaces

- User-visible changes, including some breaking changes

- Internal changes

All of the above are detailed here:

https://github.com/luarocks/luarocks/blob/master/CHANGELOG.md

I’ll try to write up more documentation between now and the final release. Feedback is wanted regarding what needs to be documented/explained! And help updating the wiki is especially welcome.

And without further ado, the tarball for Unix is here:

https://luarocks.github.io/luarocks/releases/luarocks-3.0.0beta1.tar.gz

This release contains new code by Thijs Schreijer, George Roman, Peter Melnichenko, Kim Alvefur, Alec Larson, Evgeny Shulgin, Michal Cichra, Daniel Hahler, and myself.

Very special thanks to my employer Kong, for sponsoring my work on LuaRocks over the last year and making this release possible. Thanks also to my colleagues Aapo Talvensaari and Enrique García Cota for helping out with some last-minute testing.

In the name of everyone in the LuaRocks development team, thank you for the continued amazing support that Lua community has been giving LuaRocks over the years: keep on rockin’!

Cheers!!!

Follow

🐘 Mastodon ▪ RSS (English), RSS (português), RSS (todos / all)

Last 10 entries

- Aniversário do Hisham 2025

- The aesthetics of color palettes

- Western civilization

- Why I no longer say "conservative" when I mean "cautious"

- Sorting "git branch" with most recent branches last

- Frustrating Software

- What every programmer should know about what every programmer should know

- A degradação da web em tempos de IA não é acidental

- There are two very different things called "package managers"

- Last day at Kong