🔗 The danger of simple examples

When discussing language syntax, people often resort to small examples using simple variables like foo or x, almost like “meta-syntactic variables”, i.e., to make clear these tokens are outside of the syntax under discussion.

One dangerous side-effect, though, is that these variables are always short and sweet. And syntax that works well with short variables doesn’t always work as well in real-world situations where they have to deal with the rest of the language.

Case the first

Recently we were discussing multiple assignment style in the Lua mailing list. Someone suggested this:

local a, b, c, d =

e, f, g, h

…which makes the assignments “more parallel” than a single line and avoid writing lots of locals.

I think this a case where the over-simplified example is misleading.

With real-world looking variables, it would look more like

local cfg, constraints, module_name, initial_path =

"default_config", {}, get_module_name(ctx), "/etc/myapp/default.config"

So yeah, It looks pretty with a, b, c but in the real world with significant names, this becomes a pain to maintain, and when we stuff too much in a single line, diffs are harder to read.

Case the second

Things always look good in tiny examples with single-letter variables. Which brings me to a gripe I have with an often-suggested Lua idiom: the famous t[#t+1] = v to append to arrays.

The reason why I think it’s so disengenious to defend t[#t+1] = v as the preferred idiom for appending to an array is because it looks good with a single-letter variable and five-line tutorial examples, but in the real world we use nested tables. In the end, table.insert(my.nested[data], v) is both more readable and avoids repetition:

- it’s one thing less to have a typo on

- one thing less to change

- and one thing less to get out of sync.

Note how it’s not even necessarily shorter: in this realistic example the variable name dominates the size of the statement:

table.insert(my.nested[data], val) my.nested[data][#my.nested[data] + 1] = val

Do I think table.insert is too long? Yes I do, I wouldn’t mind having a shorter idiom (many were proposed in the Lua list over the years, most of them were fine, but I’m not getting into them because we risk delving into syntactic bikeshedding again, so let’s avoid that).

Do I think it’s worth it to add local tinsert = table.insert to every program? No, I think this is worse than the t[#t+1] = v idiom, because I hate having to guess which abbreviation the module author used to write a shorter table.insert in their code (I’ve even seen local append = table.insert in the wild!). And then again, the abbreviation doesn’t gain us much: being comfortable to read is more important than being comfortable to write, but being easy to maintain is just as important if not more.

And yes, it is important to ponder what are the differences between being “easy to read”, “easy to write” and “easy to maintain”. And when pondering those, watch out for misleading short variables in the examples!

Of course, some idioms are advisable specifically for when you have short variables:

local r, g, b = 0, 255, 0

Everyone can easily read what’s going on there. But note that, almost without noticing, I also used a realistic example here! Realistic examples help getting the discussion grounded, and I find that they are often lacking when discussing syntax.

PS: And before someone mentions, the performance gains for localizing such variables as local tinsert = table.insert are overstated:

- When done at the top of modules they become upvalues and not true locals;

- Most of the modules I’ve seen doing this are far from being aimed at performance-intensive tasks that would warrant this kind of micro-optimization;

- Optimization advice changes between Lua implementations; while the cached local helps for interpreted Lua, it may actually hurt for LuaJIT. So just aim for clearer code. If you have an optimization problem you can measure and the local variable does bring a benefit, do it in a small scope, close to your performance-sensitive tight loop so that whoever is reading your code can understand what is going on.

🔗 Pen-and-paper Street Fighter II

I just remembered an interesting tidbit from my childhood.

Around 7th grade in school I invented a pen-and-paper version of Street Fighter II for people to play during classes.

I don’t remember the exact details, but basically I drew a grid for the screen and then I drew stick figures in it, and passed the page around.

People would write-in their moves and then I played CPU: I’d erase the stick figures and redraw in new positions, update hit/miss, update the energy meters.

I remember trying to keep it balanced and true to the game: Dhalsim’s punch and kick could hit farther but were weaker, etc. I had all of the “sprites” with the character movements pre-determined on my notebook.

The game went on sneaking a page back and forth along players and me at the back of the class. I imagine how bored out of our minds we must have been in school to enjoy playing “Street Fighter II at 0.05 frames per second”.

🔗 Fun hack to redirect stdout and stderr in order

Prologue

This is anecdote about roundabout ways to get stuff done. Pierre mentioned in the comments below that a proper way to solve this is to use unbuffer (though it does _not_ produce the exact same order as the terminal!). But if you want to read the improper way to do this, read on! :)

The story

Due to buffering, the terminal messes with the order of stdout and stderr of a program when redirecting to a file or another program. It prints the outputs of both descriptors in correct order relative to each other when printing straight to the terminal:

] ./my_program stdout line 1 stdout line 2 stderr line 1 stdout line 3 stderr line 2 stderr line 3

This doesn’t change the order:

] ./my_program 2>&1 stdout line 1 stdout line 2 stderr line 1 stdout line 3 stderr line 2 stderr line 3

but it changes the order when saving to a file or redirecting to any program:

] ./my_program 2>&1 | cat stderr line 1 stderr line 2 stderr line 3 stdout line 1 stdout line 2 stdout line 3

This behavior is the same in three shells I tested (bash, zsh, dash).

A weird “solution”

I wanted to save the log while preserving the order of events. So I ended up with this evil hack:

] strace -ewrite -o trace.txt -s 2048 ./my_program; sed 's,^[^"]*"\(.*\)"[^"]*$,\1,g;s,\\n,,g;' trace.txt > mytrace.txt ] cat mytrace.txt stdout line 1 stdout line 2 stderr line 1 stdout line 3 stderr line 2 stderr line 3 +++ exited with 0 +++

It turns out that strace does log each write in the correct order, so I’m catching the write syscall.

Note the limitations: it truncates lines to 2048 characters (good enough for my logs) and I was simply cutting off n and not cleaning up any other escape characters. But it worked well enough so I could read my ordered logs in a text editor!

🔗 You can’t automate SemVer, or: There is no way around Rice’s Theorem

Rice’s Theorem, proved in 1951, states that it is impossible to write a program that performs precisely any non-trivial analysis of the execution of other programs. More precisely, that’s impossible to code an analyzer for some non-trivial property that is able to decide whether an any given analyzed program has that property or not. And by “trivial property” we mean a property that either _all_ algorithms in the world have or _none_ has. So, yeah, “non-trivial property” is basically any property you can think of: “does it ever calculate 5 + 2”, “does it always use less than 10MB of memory”, “does it ever print something to the screen”, “does it ever access the network”?

At this point you might say “wait! I can write a program that checks if programs access the network or not! We can parse the code and if there are no calls whatsoever in it to any networking code such as connect(), then it doesn’t access the network!”. Sure, you can do that: but if the code has calls to connect(), you can’t decide for sure that it will access the network when it’s executed.

In 1936 Alan Turing proved that it is impossible to write a program that solves the Halting Problem, that is, to write an analyzer that checks programs and tells if it always terminates (”halts”) or it might enter an endless loop given some specific input. Okay, that’s a classic result, but that’s one property, how can Rice’s Theorem say we can’t make an analyzer for any property at all, even the silliest ones?

The proof for this amazingly powerful theorem is surprisingly simple. Turns out that if we had an analyzer for any silly property, we could use it to make a Halting Problem analyzer (which Turing proved to be impossible). Like this:

bool my_halting_problem_analyzer(Code analyzedProgram) {

Code modifiedProgram = analyzedProgram + "; someCodeWithSillyProperty();"

return my_silly_property_analyzer(modifiedProgram);

}

If the code in analyzedProgram always terminates, then the code in modifiedProgram will always reach the part that has the silly property, so my_silly_property_analyzer will return true, and my_halting_problem_analyzer returns true as well. If there is some input that makes the analyzedProgram hang in a loop, that means there’s some input that makes the silly property fail, resulting in false. Yay, we solved the Halting Problem using the silly property analyzer! Not.

Of course, this explanation is quite simplified1, so head to Wikipedia and your favorite formal languages book for the precise details. But the point stands that general semantic analysis of programs is impossible.

In particular, you can’t write a program that takes versions 1.0 and 1.1 of any program X and answer the question: “do they behave the same?”. In other words, it’s impossible to write an analyzer that looks at your master branch before you make a release and answers the question “should your new release tag be a major, minor or tiny release” according to the rules of SemVer (or any other API-compatibility-bound set of rules, for that matter).

This is because API compatibility is not only based on syntactically-expressible issues (that is, type signatures for functions and data structures). Any semantic changes to the code also break compatibility. A function may change its behavior but not its type signature (it still returns a string, but it used to be lower-case and it’s now upper-case), a struct can change they way it is used but the fields remain the same (field foo returned numbers from 0 to 10 and -1 when executed on Sundays, now it returns -1 on Saturdays as well). An automated tool won’t catch all this.

So, it is possible only to write a “pessimistic” tool, that may detect lots of situations syntactically and give the bad news: “hey, you must increment the major version here!”. But you can’t write a tool that is always able to look at code semantically and say the good news: “I assure you that no API behaviors have changed, you can safely name this a tiny version increase.”2

Yes, you can use test suites as an approximation for detecting semantic changes in API behaviors beyond type signatures and data structures. That would certainly improve your pessimistic analyzer — you’d be able to detect more situations where “you must increment major”. But even then it can only go so far, because in practice one can’t test for every possible input/output combination, so you still can’t be 100% sure. fuzz testing has uncovered bugs and unexpected behaviors even in programs with extensive test suites; as Dijkstra famously said, “Testing shows the presence, not the absence of bugs.” — likewise, test suites can show inconsistencies to the API specification, but not their adherence. So they can’t be taken to represent the semantics of a program entirely.

Anyway, in the end of the day, Rice’s Theorem shows us that general bullet-proof analysis of program behavior is not attainable, so no tool will ever be able to compare codebases and always tell us precisely that a new release is really “tiny-safe”. Semantic versioning just can’t be automated.

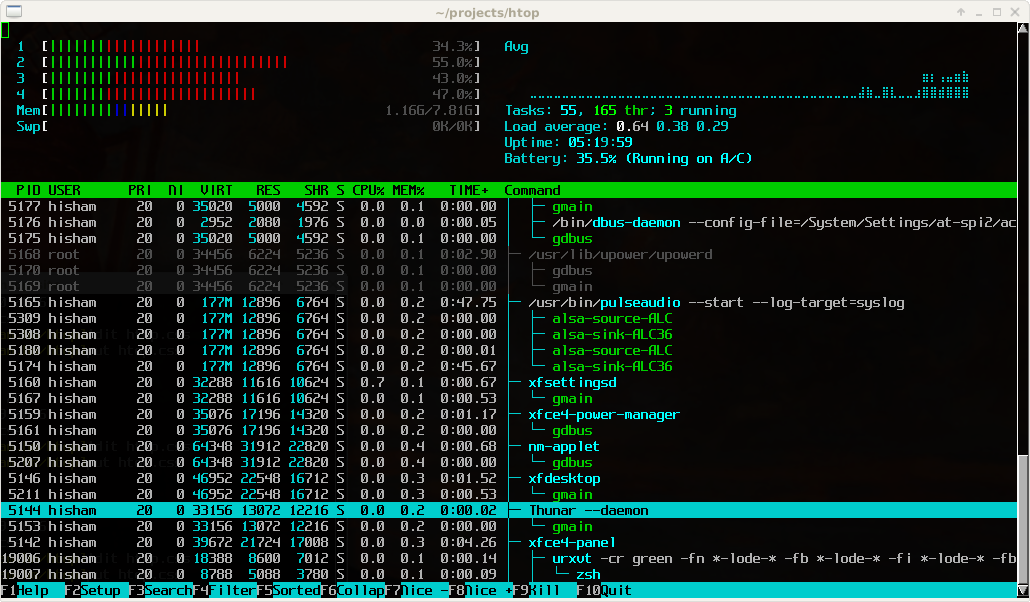

🔗 htop 2.0 released!

This week I finally released htop 2.0.0!

- htop-2.0.0.tar.gz

MD5 06f76c7d644ce8ae611c9feb10439a30SHA-256 d15ca2a0abd6d91d6d17fd685043929cfe7aa91199a9f4b3ebbb370a2c2424b5

What’s new in htop 2.0

Since version 2.0, htop is now cross-platform!

Check out the video and slides of my presentation at FOSDEM 2016

about how this came to be. This release includes code supporting Linux, FreeBSD, OpenBSD and Mac OS X.

There are also, of course, some new features:

- If you’re using NCurses 6, htop will also support your mouse wheel for scrolling.

- Moving meters and columns around in the setup screen is a lot more comfortable now.

- You can now press “e” to see the set of environment variables for a process.

- The “graph” mode for meters was revamped, inspired by James Hall’s vtop.

…And of course, lots of other tweaks and fixes!

Changelog

The changelog with the main new changes follows below. Special thanks

to everyone who contributed for this release, through bug reports, bug

fixes, new features and financial support for the platform abstraction

layer project!

- Platform abstraction layer

- Initial FreeBSD support

- Initial Mac OS X support

(thanks to David Hunt) - Swap meter for Mac OSX

(thanks to Ștefan Rusu) - OpenBSD port

(thanks to Michael McConville) - FreeBSD support improvements

(thanks to Martin Misuth) - Support for NCurses 6 ABI, including mouse wheel support

- Much improved mouse responsiveness

- Process environment variables screen

(thanks to Michael Klein) - Higher-resolution UTF-8 based Graph mode

(Thanks to James Hall from vtop for the idea!) - Show program path settings

(thanks to Tobias Geerinckx-Rice) - BUGFIX: Fix crash when scrolling an empty filtered list.

- Use dynamic units for text display, and several fixes

(thanks to Christian Hesse) - BUGFIX: fix error caused by overflow in usertime calculation.

(thanks to Patrick Marlier) - Catch all memory allocation errors

(thanks to Michael McConville for the push) -

Several tweaks and bugfixes

(See the Git log for details and contributors!)

Follow

🐘 Mastodon ▪ RSS (English), RSS (português), RSS (todos / all)

Last 10 entries

- Aniversário do Hisham 2025

- The aesthetics of color palettes

- Western civilization

- Why I no longer say "conservative" when I mean "cautious"

- Sorting "git branch" with most recent branches last

- Frustrating Software

- What every programmer should know about what every programmer should know

- A degradação da web em tempos de IA não é acidental

- There are two very different things called "package managers"

- Last day at Kong